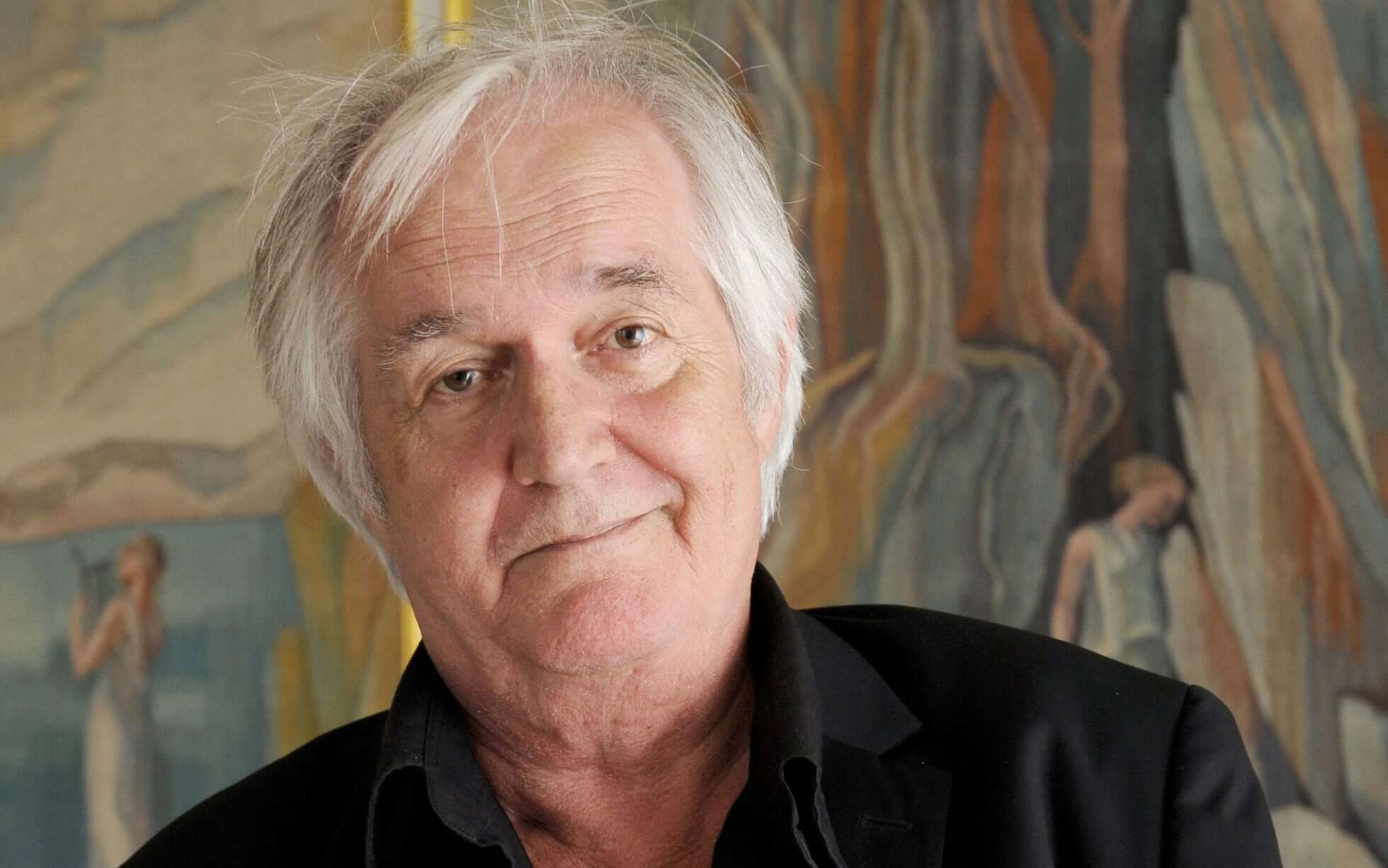

A life in writing with Henning Mankell

Widely recognized as the “Dean of Scandinavian Noir,” Swedish author Henning Mankell didn’t publish his first crime novel, The Faceless Killers (1991), until he was 43 years old. But he got his literary start much earlier, when he dropped out of school at age 16 and went to sea with the merchant marines—a time he characterized as “a romantic Conradian dream of escape” interspersed with periods of hard work and boredom.

Mankell considered his formative years at sea his “real university,” and by his 20th birthday he had returned to Sweden as a rising young playwright in a traveling theater company.

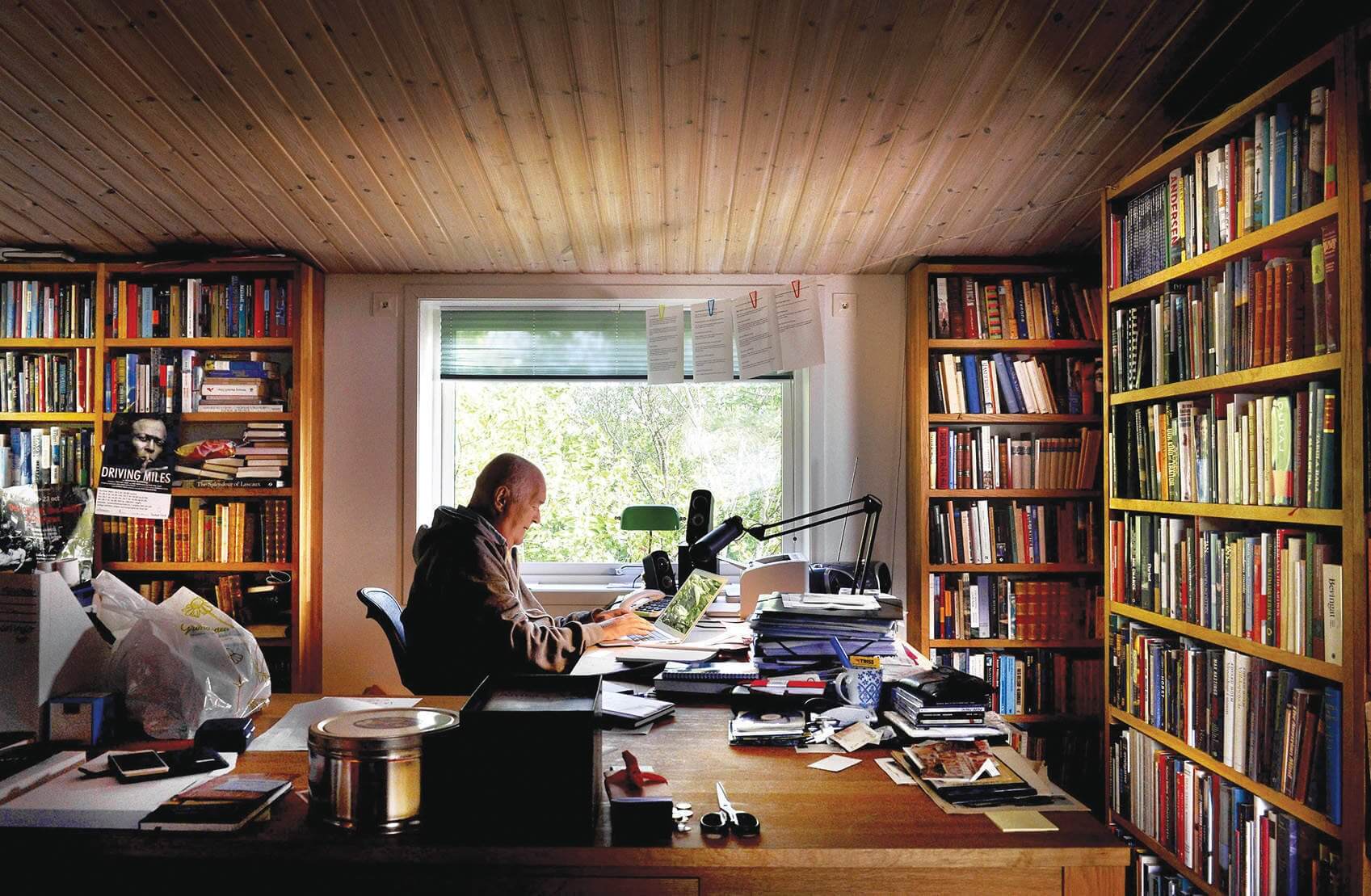

Mankell claimed that his desire to be a writer originated with his “voracious” childhood reading habit. The son of a lawyer, Mankell moved with his father and sister to the small town of Sveg, Sweden, after his mother left the family when he was one year old.

Living above the courthouse where his father served as a district court judge, Mankell read everything he could get his hands on. He found that, with the help of his imagination, he could fill in the gaps left by his missing mother. “I work best when imagination is as valuable as reality,” he later said.

A committed social activist, Mankell participated in the 1968 Paris student uprisings and wrote his first novel, The Stone Blaster (1973), about the Swedish labour movement. The royalties paid for a flight to Guinea-Bissau, a life-changing trip about which he wrote in the New York Times: “I came to Africa with one purpose: I wanted to see the world outside the perspective of European egocentricity. I could have chosen Asia or South America. I ended up in Africa because the plane ticket was cheapest.”

Happenstance may have played a part, but Mankell committed to Africa and its people in a way few Westerners ever do. For many years, he divided his time between Sweden and Mozambique, where he founded and ran a local theater company. He was a huge supporter of efforts to fight the AIDS epidemic, and campaigned to raise literacy rates and to rid the continent of unexploded landmines.

To grow up is to wonder about things; to be grown up is to slowly forget the things you wondered about as a child.

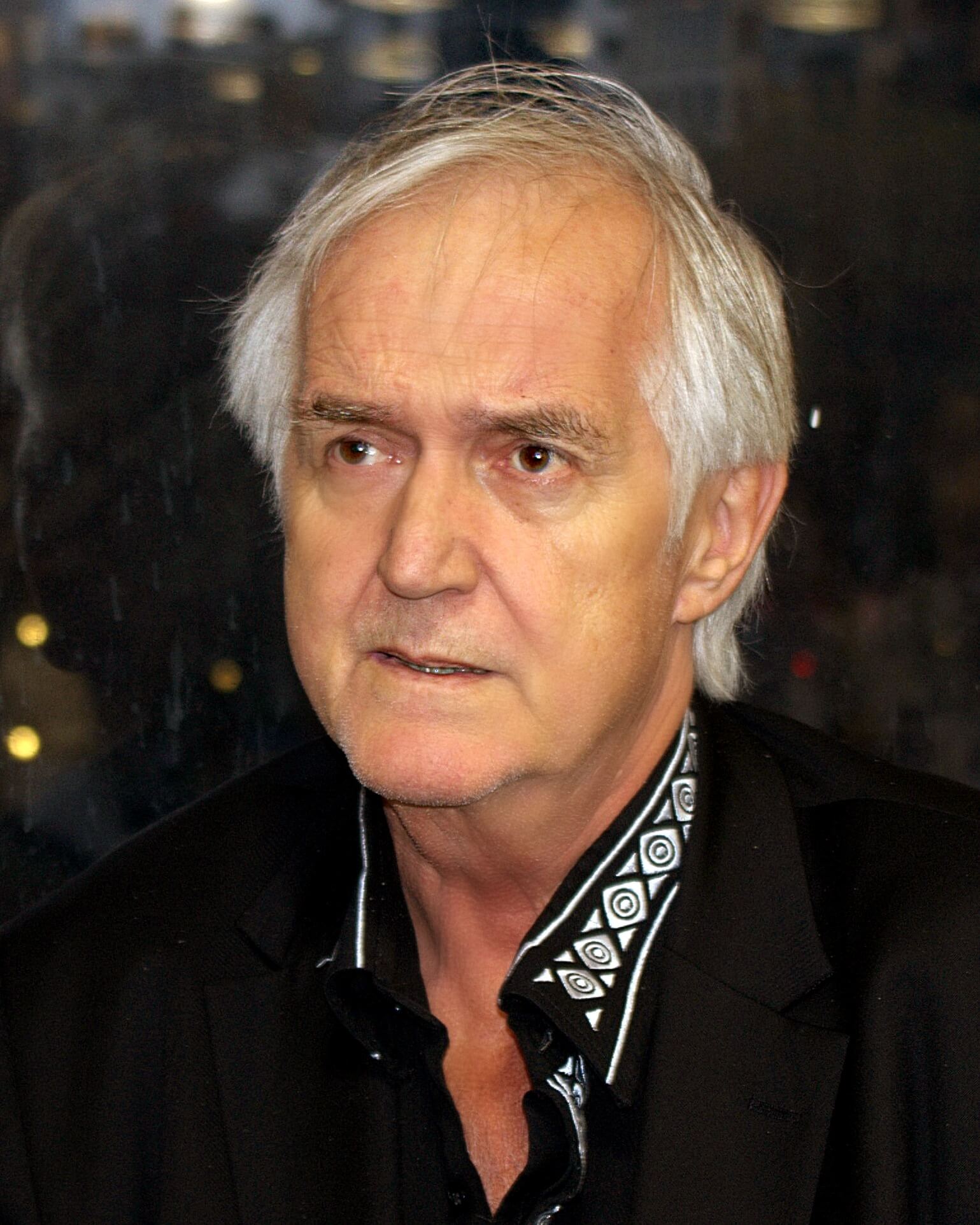

Mankell’s experiences in Africa also opened his eyes to the faults in Swedish society. He considered the Sweden of his childhood to be a happy society built on the liberal ideals of economic equality and racial tolerance. But by the 1970s and 80s, anti-immigrant sentiment was on the rise and the halls of power were rife with corruption.

Mankell’s desire to expose these issues led to his finest creation: The melancholic, alcoholic, diabetic, junk food-addicted Kurt Wallander, Chief Inspector of the Ystad police department.

An opera lover frequently unlucky in love (much like Mankell, who was married four times), Wallander brings a grumpy demeanor and a dogged persistence to his investigations, which frequently start in the small port city on the Swedish coast and expand into global affairs.

Mankell’s desire to expose these issues led to his finest creation: The melancholic, alcoholic, diabetic, junk food-addicted Kurt Wallander, Chief Inspector of the Ystad police department. An opera lover frequently unlucky in love (much like Mankell, who was married four times), Wallander brings a grumpy demeanor and a dogged persistence to his investigations, which frequently start in the small port city on the Swedish coast and expand into global affairs.

Mankell’s brilliant melding of social justice issues—poverty, racism, political corruption, colonialism, sexism, etc.—and the gritty atmosphere of American police procedurals bridged the gap between the novels of Swedish masters Per Wahlöö and Maj Sjöwall and a younger generation of writers who turned Scandinavian noir into a worldwide phenomenon, including Jussi Adler-Olsen (Denmark), Stieg Larsson (Sweden), and Jo Nesbø (Norway).

Mankell died of cancer at the age of 67. He’d already retired Kurt Wallander, in The Troubled Man (published in Sweden in 2009 and translated into English in 2011), a brilliantly plotted procedural that ties together an elderly couple’s disappearance and a Cold War-era espionage mystery. At the end of the novel, Wallander is facing the onset of dementia. It’s a fight that his millions of fans all over the world won’t get to see him win, but in these 13 thrilling Henning Mankell books, readers can rejoice that Wallander and the author's other crime fighting characters are on the case and fighting for justice.

Henning Mankell in numbers

Mankell wrote 39 books in his career as well as 44 plays. Of the 17 crime novels he wrote, 13 were about Kurt Wallander with 1 being about Linda his daughter. Mankell also wrote 8 children's books. His work brought him 11 awards.

Back

Back